History

first generation apple growers

Kordick Family Farm is a mother-daughter operation that was founded in 2009, when we planted our first 850 apple trees in Stokes County, NC. We primarily grow heirloom, regional, and cider apple varieties, with several grafted from local sources.

At a time when most commercial orchards are moving towards high-density dwarf variety plantings of trees, our MM111 semi-dwarf trees…

…are huge by current standards, the kind of tall, sprawling trees that used to be the norm in American orchards. Growing to about 20 feet high and spaced about 16 feet apart, they require ladders to pick the fruit, but aesthetically, we just like big apple trees that you can climb in, as well as the idea that they will be here long after we’re gone. And practically-speaking, our large trees are much more hardy and self-reliant than dwarf varieties, which is always a plus in a two-person operation.

In recent years, we have expanded our apple orchard to include about 1,800 trees total, representing about 175 different apple varieties. We still graft every single apple tree we plant. We also have a small pear orchard and handfuls of other fruits, including peaches, plums, figs, che fruit, and blackberries, planted on the farm. In coming years, we will be expanding our pear planting, and are always interested in adding more tree fruits (some familiar, and some quite exotic) into the mix.

Heirloom

Our Apples

We currently grow about 200 different heirloom apple cultivars, consisting of cider varieties from around the world, Southeastern regional favorites, as well as New England classics. It sounds like a lot of varieties, and it is by modern orchard standards, but there are actually thousands of apple varieties in existence. Sorry, you won’t find any Honeycrisp or modern trademarked apples in our orchard!

You will find these varieties, however . . .

Alexander

Almata

American Golden Russet

American Pippin

American Summer Pearmain

Anise Russet

Antonovka (3 cultivars from Walden Heights)

Api Etoile

Appomattox Golden Sweet

Airlie’s Redflesh

Arkansas Black

Arkansas Sweet

Aroostock Sunset

Ashmead’s Kernel

Atkins Crab

Aunt Cora’s Yard Apple

Baba Yaga (unknown from KFF, probably named variety)

Baldwin

Ben Davis

Benham

Benoni

Bevan’s Favorite

Black Gilliflower

Blacktwig

Blue Pearmain

Blue Ridge King

Bryson’s Seedling

Buckingham

Bulmer’s Norman

Bramley’s Seedling

Brushy Mountain Limbertwig

Buff

Burford’s Redflesh

Calville Blanc d’hiver

Calvin

Cannon Pearmain

Carter’s Blue

Centennial Crab

Chenango Strawberry

Chestnut Crab

Chimney Apple

Christmas Delight

Cinnamon Spice

Claygate Pearmain

Cole’s Quince

Cornish Gilliflower

Cotton

Cox’s Orange Pippin

Crispin (from Haight’s)

Crittenden Crab

Dabinette

Denniston Red

Detroit Red

Devonshire

Dolgo Crab

Domaines

Dorsey

Duchess of Oldenburg

Early Harvest

Esopus Spitzenburg

Fallawater Pippin

Fameuse

Father Abraham

Fillbarrel

Florina

Fox

Foxwhelp (nope, Fauxwhelp)

Gano

Geneva Crab

Giant Tart Summer Frying Apple

Gilpin

Gnarled Chapman

Golden Harvey

Golden Pearmain

Grady’s Fave

Green Gravenstein

Grimes Golden

Harrison

Hawaii

Hewe’s Crab

Hightop Sweet

Honey Cider

Horse (3 different sources)

Hubbardston’s Nonesuch

Hunge

Malus hupehensis aka Chinese Tea Crab

Hurlbutt

Husk Sweet

Hyslop Crab

Ingram

Inman Crab

Joyce Acres Black (unknown from KFF, probably named variety)

Joyce Acres Yellow (unknown from KFF, probably named variety)

July Tart

Junaluska

Keener Seedling

Kidd’s Orange Red

King David

King Luscious

Kingston Black

Lady

Liberty

Lowry

Loyalist

Maiden’s Blush

Magnum Bonum

Mammoth Blacktwig

Mary Reid

May

Melanie

Michelin

Milam

Mill Rose

Myer’s Royal Limbertwig

Newtown Pippin

Nodhead

Northern Spy

Nutmeg

Old Gold

Old Nonpareil

Pilot

Pink Pearl

Pomme Gris

Porter

Priscilla

Ralls

Red Astrakhan

Redfield

Red Gravenstein

Red Limbertwig

Rhode Island Greening

Rockingham Red

Rose Blush Sweet Crab

Royal Limbertwig

Roxbury Russet

Rustycoat

Sargent Crab

Shockley

Slovianka

Smith’s Seedling

Smokehouse

Stayman’s Winesap

St. Edmund’s Pippin

Stoneville Crab

Summer Banana

Summer King

Sunday Sweet

Swaar

Tarbutton

Tenderskin

Terry Winter

Tolman Sweet

Tompkin’s County King

Tremlett’s Bitter

Vandevere

Vilberie

Virginia Gold

Virginia Beauty

Virginia Winesap

Wagener

Wealthy

Western Beauty

Westfield Seek No Further

Whitney Crab

White Jersey

Wickson Crab

William’s Favorite

Wine

Winecrisp

Winter Banana

Wolf River

Yankee Sweet

Yarlington Mill

Yates

York Imperial

Yellow Gravenstein

Yellow Transparent

Zabergau Reinette

Baba Yaga

Baba Yaga's Apples of Eternal Youth story

The first members of our family to emigrate from Russia to the United States came in the early 1900’s by way of Ellis Island. They settled in a Northeastern mill town and eventually started a small dairy and subsistence farm. Some of the fruit trees they planted still stand on the old homestead, and while the first Kordicks in this country became proud Americans, they also left behind an appreciation for certain Old World customs and folklore that our family continues to enjoy today . . .

Every culture seems to have a bogeyman of sorts that is held over the heads of misbehaving children, and in Russia and several other Eastern European countries, children were raised to beware lest Baba Yaga, a rugged forest witch, seize them and gobble them up. Baba Yaga features in many famous Russian stories, often as a fearsome antagonist, yet she is also frequently portrayed as simply a wise old woman (or women, as she also may be depicted as three sisters) of the woods who serves as a guide to the heroes and heroines of folklore.

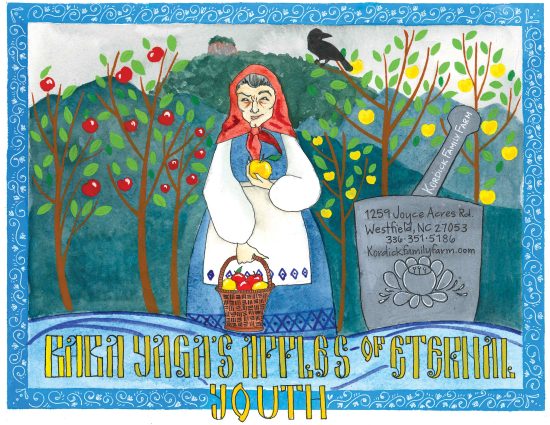

Like many apple growers of the last century, we have deliberately branded our apples with an eye-catching logo and artwork. 20th Century fruit crate labels are now collectibles, sought after for the evocative art that was meant to catch consumers’ eyes on city streets and entice them to gravitate towards one grower’s fruits over another’s.

There is a Baba Yaga fairy tale about a quest for golden apples that bring eternal youth to those who possess them, and it was this story that inspired us to stylize our apples as “Baba Yaga’s Apples of Eternal Youth,” and to come up with our own version of the story, as well as revive the old fruit crate label tradition.

We worked with Greensboro-based artist Liz McKinnon (www.heartshinestudios.com) to design a watercolor illustration of Baba Yaga with the famed apples, not in Old World Russia, but in our neck of the North Carolina foothills. As the crow flies, Kordick Family Farm is about 15 minutes north of Pilot Mountain, and we have a postcard view of the knob from the center of our property. To our west lie the Blue Ridge Mountains, while the Sauratown range borders us to the east. The Dan River is mere minutes away to the south of the farm.

HANDMADE

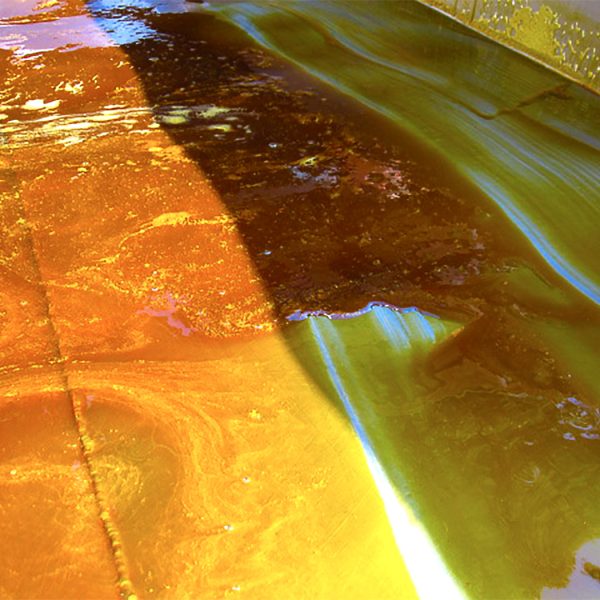

Our Apple Cider Syrup

It takes a long time for large apple trees to start bearing fruit, period. And if you’re trying to grow apples in the Southeast, it takes an even longer time to hit upon the right mix of practices to produce fruit of consistently high quality. This means we’ve had a lot of time to think about what we want to do with our apples, and smaller quantities of fruit to play around with. In this manner, we created our flagship product: Baba Yaga’s Apple Cider Syrup.

Much like hard cider, apple cider syrup was …

…an American staple in past centuries, a stable, homegrown sweetener that had endless uses. However, with the advent of granulated sugar (and probably also due to the widespread razing of American apple orchards during Prohibition), cider syrup all but disappeared from the pantry.

When we became interested in re-introducing cider syrup, we sought out the local Southern experts: sorghum syrup producers. A very generous, close-knit community, our new friends taught us the sorghum syrup-making process and helped us adapt it to cider syrup.

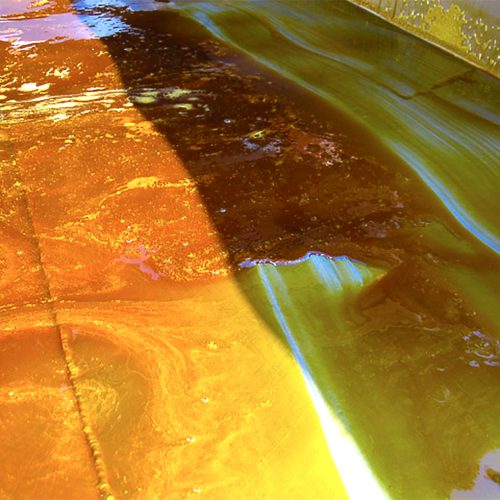

Starting with 100% farm-pressed apple juice (cider), we boil enormous pans over a wood fire for hours until it is reduced to about 1/10 of the original volume. At this point, the sugars have concentrated to form a thickened syrup that is wonderfully fragrant and tangy in apple flavor, and is ready for . . . almost anything.

Really. It is actually easier and infinitely quicker to list the things that cider syrup wouldn’t be good on (Fish? Well, some fish. It’s actually wonderful on salmon!). The most obvious, and hard-to-beat, application is to pour cider syrup over pancakes, biscuits, and other breakfast pastries. Perhaps the most unexpected use, however, is to make a braise or sauce for savory items like pork roast or sweet potato gratin/casserole. It even pairs well with salads in the form of a vinaigrette. Try drizzling it over ice cream or yogurt, spoon it on top of oatmeal, add it to popcorn . . . Beverage-wise, you can make an instant cup of hot cider by adding about 4 Tbsp (or to taste) cider syrup to a cup of hot water. Add a shot of brandy or rum to your cup, or add cider syrup to any number of cocktails and mixed drinks. Finally, cider syrup can be used in baking, much like maple syrup.

Apple cider syrup is a staple that never should have left the American kitchen.

To purchase Baba Yaga’s Apple Cider Syrup, please visit our online Etsy store or contact us to set up a time to pick up from the farm store. If you’re not close by and would prefer to pay by check, rather than go through our online store, we’d be happy to ship directly to you, and you can contact us with your information.

HOLISTIC

our growing practices

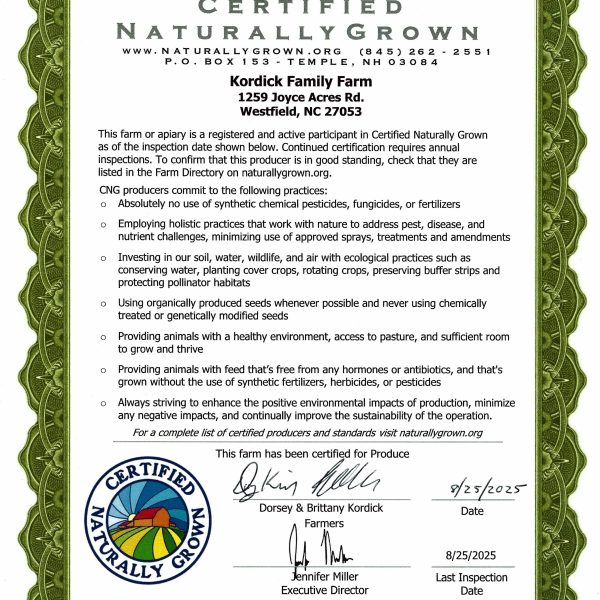

Like many unconventional farmers, we have struggled to find a term that describes our growing practices, while also communicating in a single word our management philosophy to consumers. ‘Natural’ and ‘sustainable’ mean nothing without context. ‘Low-spray’ can be used by growers who spray conventional chemicals, but at their lowest possible application rates. We are Certified Naturally Grown, and most of the materials we apply are listed by OMRI (the Organic Materials Review Institute), however, use of the term ‘organic’ implies certification, which we are not currently. We are beyond organic at this point in our growing careers, and have finally settled on the term, ‘holistic,’ in the sense championed by Michael Phillips and the Holistic Orchard Network, of which we are proud members (http://www.groworganicapples.com).

Over the years we have found the most widely available commercial formulations of organic chemicals tend to have one thing in common: it’s not so much that they work well against pests and disease and truly promote good crop health; more so, it’s that they do no harm. Low efficacy coupled with premium price tags just doesn’t cut it on our farm, and after losing apple crop after apple crop in spite of our diligent lockstep organic program, we decided we needed to find a better way to grow. We think we’ve found it. To large extent, we have stopped thinking like conventional and conventional organic growers, who are mostly concerned with preempting pest and disease pressure with preventative chemical sprays, as well as responding with curative formulations once pest and disease pressure is in evidence.

Instead, we focus on cultivating trees, and indeed, an orchard environment, of such optimal overall health that it is not as sensitive to a disease or pest outbreak, not unlike a person who eats healthy, doesn’t try to sterilize everything in sight, but maintains good hygiene, and thus is much less likely to be laid up by the latest bug going around. To that end, we nurture the root zone environment with inputs like hay and wood chips to promote a healthy fungal ecosystem that gives tree roots access to all manner of good nutrition. We also regularly apply beneficial microbes, along with fatty oils for them to feed on, to promote canopy colonization by species that work symbiotically with the tree, again to the end of excellent nutritive uptake, while also taking up space that might otherwise be “infected” by “bad” bacterial species that cause disease. And as we transition to this new way of growing, we do spray the occasional broad spectrum knockdown like copper or PerCarb, though not anywhere near as often as we did in the past, and for different purpose. Using the aforementioned chemicals as an example, when we come in and sanitize the fungal and bacterial populations with a tree spray, we don’t leave it that way and then try to maintain a sterile environment with regular subsequent sprays. What we want is to start with a clean slate for an application of beneficial microbes and to nurture this population for as long as possible. It’s all about using your tools wisely, and as it gets harder and harder to grow fruit period, we need an effective grower’s toolbox.

This is not our great-grandparents’ farmstead orchard. In the early and mid 20th Century, they simply did not have the disease and pest pressures that have spread with globalization. Also, people back then did not put quite so high a premium on fresh fruit appearance. Nowadays there are so many potential and wide-ranging issues to worry about it makes our heads spin. Unsurprisingly, the West Coast of the United States is a much more ideal environment for growing apples in general, and organic apples in particular. Plum curculio, one of the hardest pests for organic East Coast growers to control, doesn’t occur in the western half of North America, and until recently, fireblight, a devastating bacterial disease on the East Coast, wasn’t an issue either. Throwing in the endemic fungal disease smorgasbord of the humid South makes it especially tricky, to say the least, for apple growers in the Southeast who are trying to maintain a remotely organic orchard.

A lot goes into orchard management. As mentioned above, we mulch with hay whenever possible for weed suppression and cultivation of a healthy root zone. We utilize untreated trap crops and sacrifice the fruit to certain pests in the hope that it prevents them from entering the orchard proper and causing damage. We collect fallen apples and diseased prunings for burning so they don’t serve as vectors for future pest and disease development. In short, we do everything we can to reduce the need to spray — indeed, it’s a rare grower who is enthusiastic about spraying anything. Whether you’re spraying conventional or unconventional nutrients, pesticides, fungicides, herbicides, or even beneficial bacteria, it’s a time-consuming, fuel-eating, equipment-wearing hassle, and often a very expensive and potentially dangerous one. If a farmer is spraying anything, it’s because he or she truly thinks their crop and livelihood depends on it. Talk to us — most farmers would love a chance to have an honest discussion about growing practices rather than be bound by the are-you-organic-or-not litmus test.

Organic chemicals and materials can be abused as much as conventional ones, can be just as bad for pollinators, and can also accumulate to the detriment of the environment. In addition, decreased efficacy often means increased application. You can go out of your way to avoid synthetic chemicals derived from fossil fuels, but if you have to spend more time on your tractor burning fuel and compacting the soil in order to apply them, is that sustainable? Rather than lecture you on our definition of sustainability, we will keep an updated list on this website of what materials we use in our orchard and why, as well as this discussion of practices, as it evolves, and you can decide for yourself if this meets your definition of sustainability.

We maintain mason bee houses in the orchard, as well as honeybees and pastured rabbits. If we wear any safety clothing/masks while spraying, it’s generally to keep from getting soaked and cold and filthy. We don’t spray anything that we consider unsafe to our bees, livestock, or ourselves. For the 2025 growing season, we will be deploying:

fruit bags: from Clemson University, our only domestic source of paper fruit protection bags; it’s a lot of work, but we love bagging some of our most problematic apple varieties to provide a physical barrier against pests, diseases, deer, hail, sunburn, you name it. We highly recommend these bags for homeowners who want high quality fruit without management hassle throughout the season. Literally, lightly waxed, thin, white paper bags with a tiny wire to hold the bag closed over the apple. We burn the bags in our woodstove for firestarter in the winter.

Delta insect monitoring traps: we hang Delta sticky traps in the orchard at the beginning of the orchard and add various insect pest pheromones and plant compounds to attract pest species we’d like to monitor for IPM (Integrated Pest Management) purposes. If numbers stay below a certain threshold, we know we don’t need to take action to control a pest, but if they do cross the threshold, we can better pinpoint our control measures to suit population numbers and life stages.

Circle plum curculio traps: an ingenious trap constructed of screen, a plastic funnel with collection chamber, wood, and some twine. We tie these traps around “trap” trees and our historically worst curculio-afflicted trees and bait them with plum essence and wintergreen oil to entice curculio adults in, then check daily to squash curculio and release “bycatch” insects

Isomate CM/OFM mating disruptors: we hang these OMRI-listed dispensers in our trees before bloom; they are laced with Oriental Fruit Moth and Codling Moth pheromones and overwhelm the male and female moths, preventing them from finding each other and mating

Madex HP: Cydia pomonella, an OMRI-listed granulovirus that is super-specific to Codling Moth and Oriental Fruit Moth; we apply this in blocks where mating disruption wasn’t enough to prevent high populations of OFM

Regalia: OMRI-listed, this Giant Knotweed Extract formulation activates ISR (or induced systemic resistance) in a plant to help strengthen its natural defenses during times of stress, high disease risk, etc.

Romeo: an OMRI-listed derivative of everyone’s favorite yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (used to make wine, beer, and cider), consisting of “cerevisane,” the cell walls of S. cerevisiae. Used to stimulate an ISR (induced systemic resistance) response in the trees pre-disease event, so they react early and strongly when pathogens strike.

AgriPhage: OMRI-listed, contains bacteriophages that specifically target the bacterium responsible for fireblight. After several years of steadily increasing fireblight pressure in the orchard, we have finally found a biological product that can make even the worst shoot blight take a seat on the bus like everybody else.

Core Holistic Spray: a rotating cocktail applied four or more times a growing season for nutrition and disease/pest prevention, including some or all of the following — TerraNeem (OMRI-listed neem oil formulation; also used for spring “fatty acid knockdown” spray), Ferti-Organic karanja oil (OMRI-listed), Spectrum beneficial microbes (OMRI-listed), MaxiCrop soluble seaweed powder (OMRI-listed), AEA Micropak trace minerals (OMRI-listed), blackstrap molasses (OMRI-listed), Ecos (a “plant-powered” dish soap that we use to help emulsify the brew components)

Isomate mating disruptors: OMRI-listed dispensers that are hung from tree canopies to release mating pheromones of Oriental fruit moth and codling moth to make it harder for adults to find each other and reproduce within the orchard.

Lime Sulfur: OMRI-listed, but our least favorite thing in the world to spray! It is very caustic and can cause severe corrosion on equipment and our persons (burns), but it is very useful when severe broad-spectrum disease clean-up is needed in the orchard during dormant season. Can also be used as to thin blossoms during bloomtime, but of course, it also kills beneficial fungi and bacteria. For that reason, it is often used pre-beneficial biological applications to create a blank slate to start from. We will be applying it in late fall post-harvest to prevent Neonectria ditissima (European Apple Canker) cankers from spreading in our trees after a few bad years.

Blossom Protect/Buffer Protect: OMRI-listed strains of Aureobasidium pullulans that provide protection against early season fireblight by colonizing blossoms in a prophylactic manner and creating an inhospitable environment for fireblight-causing bacteria by acidifying the blossom interior.

Serenade ASO: OMRI-listed, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (formerly classified as Bacillus subtilus) that colonizes the tree canopies to prevent fungal pathogen infection via several modes of action

Stargus: an OMRI-listed rhizobacterium (Bacillus amyloliquefaciens) that colonizes the tree canopies to prevent fungal pathogen infection via several modes of action

Howler: an OMRI-listed Pseudomonas chlororaphis formulation that provides preventative control against fruit rot pathogens via several modes of action.

Nufilm: an OMRI-listed, pine resin-derived spreader-sticker that we sometimes add to our spray tank mixes if we know rain is coming. Also provides some protection to UV-sensitive biologicals.

Biodynamic Tree Paste: an OMRI-listed biodynamic preparation from the Josephine Porter Institute, containing bentonite clay, Pfeiffer BD field spray, Equisetum tea, etc. We like to have this on hand to treat any disease cankers or physical damage on our trees.

BotryStop: a live spore preparation of a non-pathogenic saprophytic fungus (Ulocladium oudemansii (U3 Strain). This OMRI-listed sap fungus is particularly aggressive at colonizing dead or dying tissue, and we’ve started applying it after bad fireblight or nectria dieback, as well as to pruning cuts, to prevent pathogens that favor dead tissue from establishing

Nitryx: an OMRI-listed nitrogen-fixing bacteria that we inject into the soil beneath the apple trees. Paenibacillus polymyxa P2b-2R colonizes the apple roots and fixes nitrogen from the atmosphere to increase the amount of plant-available N in the soil.

Surround: that “white stuff” you see covering the trees of organic orchards is just OMRI-listed kaolin clay! When applied to the canopy, the clay effectively scatters the sunlight hitting the trees’ leaves, reducing sunburn to fruit and heat stress to the tree in general. Too much trouble to apply to the orchard at large, but we use it in a couple of our varietal blocks most susceptible to heat damage.

Endomycorrhizal Inoculant: OMRI-listed endomycorrhizal fungus species in micronized powder form; we can dilute this in water to make a root dip for trees and transplants to get them off to a great symbiotic start with beneficial fungi partners

Blend Magic 40% Vinegar: non-synthetic concentrated vinegar allowed by OMRI for burndown treatment of weeds. We apply it as needed before putting down hay mulch between our apple trees.

Allganic Nitrogen Plus (15-0-2): an OMRI-listed Chilean nitrate we applied sparingly to adjust areas of the orchard low in nitrogen

Got questions or concerns? Check out our contact info further down on this page and drop us a line.

Plum curculio will be our pest of the month in perpetuity. Ah, April, when the early apple trees enter petal fall stage, fruitlets begin to develop . . . and plum curculio (Conotrachelus nenuphar) rears its ugly, little head. Plum curculio may be tiny, usually only a quarter of an inch or less in length, but it causes bigtime damage in Eastern fruit orchards every year. There are many growers who are organic in every way, save the exceptions they make to combat plum curculio. A hard-bodied, extremely tenacious weevil, its modus operandi is to overwinter in the woods surrounding orchards, then move into the orchard proper at petal fall with the goal of laying as many eggs as possible in developing fruits.

The larvae develop inside the fruitlets, causing damage one of two ways: 1) the larvae fully develop, secreting certain chemicals that make the fruitlet drop to the ground, where the grown larvae can penetrate the soil to complete the life cycle, or 2) the larvae may be crushed to death as the young fruitlet grows rapidly, leaving the initial damage from the egg deposit as a gateway for other pests and diseases. Either way, they are a major, major headache that growers have been battling for a century or more. There are neat photographs of early twentieth century growers out with large teams, literally beating the trees to shake the curculio adults onto sheets spread below the trees, to be removed from the orchard for certain destruction.

The key to controlling plum curculio is stopping the population cycle — you want to reduce the number of egg-laying adults that you will have to combat the next year, so most of the time, you’re actually targeting the larvae themselves in a number of ways.

We have planted trap crops of early-fruiting plum and peach trees so we can sacrifice the fruit to the plum curculio and target the larvae before they move into the later-fruiting apples. Sound theory, but it doesn’t always work so well since, in this area, cold springs often preclude peach, and especially plum, fruitset. So most of the plum curculio probably make it past the trap crop in any given year to the orchard proper.

The next line of defense is to apply coats of refined kaolin clay to your trees. The clay particles slough off onto curculios making their way into the trees, getting into all their orifices and irritating them. The idea is to convince them that our apple trees are just not worth the pain and suffering. But in order to be effective, kaolin clay has to be applied in a heavy and consistent enough layer, easier said than done around bloomtime, when growers are busiest and the weather is rainiest (the clay will wash off in rain, so many layers are required).

So historically, many adults do succeed in their raison d’etre, to deposit their eggs under the skin of our new apples. But we still need to target the larvae in order to prevent a larger repeat of this whole cycle the next year. Parasitic nematodes can be applied to the soil beneath trees, where they will happily gobble up plum curculio larvae after they penetrate the soil. We’ve tried this in the past and may again in the future, but for now, rely on Circle traps around the trunks of orchard perimeter trees to catch early season adults walking into the orchard each spring.

Thanks in large part to an NC AgVentures grant, we installed a RainWise weather station at the orchard in winter 2021. Having such site-specific weather data at our fingertips will help us make better management decisions. And since our information is public, local gardeners and growers can also benefit.

Check out our current weather conditions via our RainWiseNet webpage!

Check out our local pest and disease forecasts via our NEWA (Network for Environmental and Weather Applications) webpage! (Select “Westfield” from the drop-down weather station list.)

CURRENT EVENTS

Winter Work:

This time of the year stands out for some of the most essential, but least glamorous, work of orcharding: soil sampling, pruning, paperwork, planning for the 2026 season, scionwood harvest for spring grafting, general cleanup in terms of sanitation (removing any dropped and diseased fruit), mowing, and mulching with hay in between trees.

It’s a great time of the year to plant trees, so we work on establishing new plantings and plugging any holes where we’ve removed trees. We also spend way too much time putting together a scionwood wish list of way too many varieties we want to add to our ever-expanding lineup and make believe we’ll be able to find a place for them someday!

Apple Tree Grafting Workshop at Deep River Folk School in Franklinville, NC

February 21, 2026, from 1 pm to 4 pm

Join experienced apple orchardists and fruit tree grafters Brittany and Dorsey Kordick (from Kordick Family Farm) who grow many varieties of heirloom apple trees. The workshop will cover basic grafting techniques. Each participant will graft three heirloom apple trees that they will then take home with them. Expand your fruit growing experience and knowledge and also help preserve heirloom apple varieties well adapted to central North Carolina.

Please visit this event’s page on the Deep River Folk School website to sign up!

All materials are included.

This workshop is eligible for use with a season pass.

Youth, under 18, may attend free with an adult (1 youth per adult)

Early-bird pricing ($55) is available through Feb. 7. After that, the cost is $75.

This pile of stuff was once an enormous 100 year-old cider press, and soon it will be again . . . when we find the time and space to get it up and running again. Stay tuned. For now, it’s a sight to see, with all its fascinating nuts and bolts (and massive pulleys) on display in the orchard packhouse.

NEWS FROM THE APPLE BRANCH

We send out a monthly newsletter with farm happenings, heirloom apple histories, recipes, and orcharding insights. To receive “News from the Apple Branch” directly to your email inbox every month via Mailchimp, please subscribe here. Otherwise, you can enjoy elements of our most current newsletter below, as well as peruse past installments from our archives.

The countdown to the New Year has already begun, and tonight the orchardists of KFF will celebrate the start of 2026 along with the rest of the world. For us, however, January 1st mostly signifies the official start of our pruning season, and even in the years that weather precludes making the first day of the New Year a work day, it’s very important to us that we at least make a ceremonial first cut on even a single apple tree. This way, we get a jump on re-focusing our thinking to the task that will concern us most over the next three months. On your mark, get set, 5-4-3-2-1, ladies and gentlemen, sharpen your pruners, we’re off! (Well, actually, some of us have already been sneaking in a few discreet cuts here and there, a little ahead of schedule.)

For the past month, we’ve been trying to knock out as many of our various winter tasks as we can, so that as soon as January 1st rolls around, we can focus solely on pruning without worrying about other orchard distractions on the to-do list. This means, especially, taking care of any lingering orchard clean-up, in terms of mowing and weedwacking, so we have clean ground to drop, then pile, our prunings on. It also means getting any new tree plantings knocked out.

This year, our planting list included medlar trees for the first time, as we prepared an area to receive our first specimens of these pome fruits, which are in the Rosaceae, or rose, family, just like apples, pears, and quince. We are starting with two varieties, with the intent to graft many more different ones this spring for a comprehensive test row of varieties. We will monitor these for several years to see which, if any, varieties perform better for us than others before planting out a more extensive orchard of medlars.

While these old, interesting fruits share some characteristics with apples, the white spring flowers more closely resemble those of wild roses and the fruit itself, often completely russetted like many pear types, are shaped like overgrown rose hips. They are often grafted onto pear, quince, or hawthorne rootstock, but are not compatible with apple rootstocks.

Medlars are ancient fruits that were historically grown throughout what is today Europe and Asia. The fruit became popular during the Middle Ages, but due to the strangeness of its appearance (“dog’s arse” is a common descriptor throughout history and culture) and some interesting post-harvest needs, many of the written references that survive (including several plays by William Shakespeare) are not particularly flattering. Medlars are quite different from other pome fruits in that, before most forms of consumption they require a treatment known as “bletting” after harvest. This involves, essentially, letting the fruit break down for several days or weeks, as necessary until their hard, astringent flesh transforms into something more like a soft, mellow, caramelized paste, often described as resembling dates or stewed apples.

Once bletted, medlars can be enjoyed as is, or more commonly, are turned into jelly or “cheese” (fruit paste). Author Jane Steward, who literally wrote the book on medlars, gets very creative with her medlars and includes many fantastic-sounding recipes and processes (including how to make alcohol from the fruit). In recent years, medlars have begun to enjoy a resurgence among fruit enthusiasts, particularly in the United Kingdom where Mrs. Steward maintains her orchard and medlar goods business, and are no longer hard to track down in nurseries. In fact, as we increasingly seek to diversify our own nursery offerings here at KFF, we hope to be able to graft many varieties of medlars for sale going forward.

Finally, New Year’s Eve doesn’t have to mean the end of holiday parties. Consider this a friendly reminder that Twelfth Night is just around the corner on January 5th, and that means it’s wassail time! Don’t forget that, on the last of the 12 days of Christmas, it is traditional to bless your trees for the coming year with song, dance, cider, toast, and general merriment to do what you can to scare away any evil spirits lurking in the orchard and encourage a good harvest for the coming season. So locate your largest, or favorite, apple tree, or your neighbor’s, or even a wild one, and be ready to wassail for all you’re worth! If you want extra credit, you can make a special hat or dress in traditional costume to let the trees know you really care. Happy New Year and Waes Hael (Good Health)!

Hunge is a fairly obscure apple, as varieties go, which is why we initially grafted only four trees for planting out in our orchard. This seems like quite an oversight now. Easy-keeping, adaptable apple trees have always been appreciated, but as weather seems to be increasingly keeping orchardists on their toes, perhaps it has never seemed so wise to select un-fussy trees that do well in one’s particular climate. We have a winner: meet the Hunge apple.

While the birth of this variety is lost to history, it is assumed to have originated in 1700s North Carolina in Moravian settlements, and it was here in NC that Hunge experienced a modern rebirth. We find the first mention of this apple in the Downing brothers’ 1857 compendium, The Fruits and Fruit Trees of America, wherein Hunge is described as a culinary and drying apple, “popular and long cultivated in North Carolina,” albeit with “origin uncertain.” The name is listed as being synonymous with ‘Hunger,’ and rather than referring to a family name, may simple be expressing colonial slang for the term in reference to the apple’s value in staving off that worrisome condition.

In the 1850s, a Mr. S.W. Westbrook of Greensboro, NC seems to have done quite a lot for the Hunge apple, in terms of getting the fruit into the right hands, publicity-wise. This person provided fruit samples to several parties during this time period, including The American Pomological Society for consideration in 1857, and as was typical, the fruit was favorably reviewed.

Hunge was available to a limited degree by Southern nurseries in North Carolina, Virginia and Georgia in the subsequent decades, and the 1869 USDA Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture notes that the variety is “valuable in North Carolina.” By the turn of the century, Hunge had expanded its range somewhat, at least to the Midwest, where it was listed in experimental orchards at the University of Illinois and the Ohio Agricultural Experiment Station. Interestingly, the reports from both of those orchards are less than enthusiastic: from Ohio, we hear that Hunge proved “of only limited value,” and in Illinois, the fruit was deemed “not rich, only good in quality.”

Benjamin Buckman persevered with Hunge at his extensive experimental orchard in Farmingdale, Illinois, which still contained the variety in 1913. However, it appears that, for all intents and purposes, Hunge remained primarily an NC apple, but like most heirloom apples, suffered a decline in popularity and plantings as the mid 20th Century approached.

Thankfully, in 1940 a lady named Gertrude Morris grafted a scion from her father’s old Hunge tree in his Wayne County, NC orchard. She had found a seedling apple tree growing in a ditch in front of her home in Newton Grove and decided to use it to graft onto and grow a new Hunge tree. When author Lee Calhoun was seeking out old Southern apples in the 1980’s for preservation, he was contacted by Mrs. Morris regarding the Hunge apple. While Hunge enjoyed some regional popularity in the mid to late 1800s, by the end of the 20th Century the variety was all but extinct. In fact, as best as Calhoun could tell, the Hunge tree Mrs. Morris had grafted in 1940 was the last one in existence! Thanks to the efforts of Mr. Calhoun, the propagation of Hunge trees began anew, and today, several heirloom apple orchards and nurseries in the Southeast, including ours, again plant and stock Hunge trees as a matter of course. But the Hunge apple history really gets a shot in the arm when Kuffel Creek Nursery of Riverside, California contacted Horne Creek Farm, the repository of Lee Calhoun’s Southern apple collection, about obtaining scionwood of apple varieties for testing in warmer climates.

Once Hunge had proven itself in the Southern CA heat, Kuffel Creek’s owner, Kevin Hauser began shipping trees to Africa as part of the Apples for Africa aid project. Halfway around the world from its Carolina roots, Hunge is reportedly thriving; in 2013 Hauser reported that the variety is doing “particularly well in Zambia,” where the trees receive ZERO chilling hours! Perhaps Hunge’s considerable adaptability should not surprise. After all, thanks to the Morris family, we know that Hunge performed well in the sandier Coastal Plains soils of Newton Grove and Wayne County, which is unusual . . . but that’s still a long way from the tropics!

Historical sources often describe Hunge as having greenish-yellow skin sometimes with only a red blush (perhaps this was why William Coxe, a New Jersey horticulturalist, considered Hunge potentially the same apple as ‘Jersey Greening’ aka ‘Rhode Island Greening). As you can see from the picture of Hunge taken in our orchard, taken at the very end of August, with full sun exposure, it is possible to achieve entirely red fruits, eliminating the persistently green Rhode Island Greening apple as a possible synonym for Hunge in our book.

In fact, we have noticed that pictures of Hunge fruit grown in warmer climates does seem to be mostly or entirely red overlaid on green-yellow underskin, whereas the historical accounts, often deriving from cooler climate-growing, emphasize the yellow-green color. However, it does seem that, wherever it is grown, Hunge is notorious for its variability in size and color, as well as the degree to which it develops its somewhat characteristic russet netting from year to year. It is solidly mild, subacid, yet somewhat vinous in flavor, and pleasantly aromatic. Truly an all-purpose apple, there is some reference to Hunge being used in brandy, and we will look forward to experimenting with it in cidermaking in coming years.

We have to give credit where credit is due: while looking for an interesting basis for a baked, stuffed apple recipe we found this great recipe on none other than The Food Network and love it so much we barely changed a thing when writing it up here. The use of pistachios, raisins, and sausage with chopped apple makes for a tasty and elegant, slightly exotic stuffing that would be at home in winter squash, meat entrees, or by itself, but baked into an apple, it really hits the sweet spot. And do use sweet apples to complement the filling in this particular recipe; pouring a little vinegar in the bottom of your roasting pan will add enough requisite tartness. If you use smaller apples, these make wonderful finger foods.

6-10 sweet apples, depending on size

1 lb sausage

1 Tablespoon olive oil

1 shallot minced

2 oz. Calvados, or any brandy

1/2 cup golden raisins

1/2 cup pistachios, toasted and chopped

2 Tablespoons of fresh sage, thinly sliced

salt and pepper

about a cup of rice wine vinegar (or slightly dilute white or apple cider vinegar with water)

Cut the apples in half and hollow out the halves: use a melon baller or small scoop to remove the hard parts of the core, then scrape out most of the apple flesh and reserve this, leaving 1/4 to 1/8 of an inch layer of apple flesh within the skin shell. Chop up the apple flesh you remove and set aside.

Preheat your oven to 350 degrees F. Saute the sausage in the olive oil for about 5 minutes, then add the shallot and cook for a further 5 minutes. Deglaze your pan with the Calvados or brandy. Remove from heat, then add the raisins, pistachios, sage, salt and pepper, as well as your chopped apple.

Set aside briefly until cool enough to handle comfortably, then stuff your apple halves with this filling, pressing it down with a spoon or your fingers, leaving it slightly mounded out of the apple shell. Arrange the halves in a roasting pan, skin-side down, then pour the vinegar around the apples. Bake, uncovered, for 25-45 minutes, depending on the size of the apples (check the firmness of the apple shell). Enjoy warm.

Cider Syrup

Recipes

Apple cider syrup is the perfect base for a sweet and tangy barbecue sauce. This full-flavored recipe packs just a hint of heat and makes 2 cups of sauce.

1 cup Baba Yaga’s Apple Cider Syrup

1/2 cup apple cider vinegar

1/2 cup tomato paste

2 Tablespoons grated onion

2 cloves garlic, minced

2 teaspoons fresh grated ginger

2 teaspoons prepared (not dry) mustard

salt to taste

dash of cayenne pepper

Whisk all ingredients together until smooth. Then you know what to do: baste all over your favorite protein and grill, bake, or broil it up.

(adapted from an Our State Magazine recipe and shared by our friend, Randy)

4 Tablespoons (or to taste) Baba Yaga’s Apple Cider Syrup

1 pound Brussels sprouts, trimmed and halved

2 Tablespoons olive oil

1/2 teaspoon salt

pepper to taste

1 large, decent apple, peeled, cored, and cut into cubes

(the original recipe calls for Granny Smith or Honeycrisp apples)

Preheat oven to 400°. In a large mixing bowl, toss Brussels sprouts with olive oil and season with salt and pepper. Spread on a parchment-lined baking sheet. Roast for 15 minutes, tossing once during cooking time.

Remove sprouts from oven, then toss them in the cider syrup and add apples. Spread the sprouts and apples back on baking sheet and return to oven for 10 minutes or until tender. Check seasoning; add salt and pepper to taste. Serve hot or at room temperature.

Reminiscent of lemon meringue pie!

1 cup Baba Yaga’s Cider Syrup

2 eggs

3/4 cup milk

1/3 cup sugar

3 Tablespoons flour

1 standard pie crust

Mix all ingredients together with handbeater or blender until smooth. Pour into crust and bake at 350 degrees about 45 minutes, until set and slightly browned on top.

Makes about 75 pieces of decadent apple candy!

2 cups cream (heavy, whipping, or even coconut)

1 cup light corn syrup

2 cups sugar

1/2 cup Baba Yaga’s Cider Syrup

6 Tablespoons butter

1/2 teaspoon salt

spices (1/2 teaspoon cinnamon, 1/4 teaspoon ginger, 1/8 teaspoon allspice, and 1/8 teaspoon nutmeg)

Lightly grease an 8 inch by 8 inch baking pan and line with parchment paper, leaving an overhang on all sides.

In a heavy-bottomed pot, combine cream, corn syrup, sugar, cider syrup, and butter. On high heat, bring to a boil, stirring only until sugar dissolves.

Reduce to medium-high heat and cook without stirring until the temperature reaches 248 degrees on a candy thermometer, about 30 minutes. Remove the pan from heat and stir in salt and spices.

Pour into the lined pan and let sit at room temperature for about 18 hours without disturbing.

Remove from pan and cut into desired bite-sizes (about 3/4 inch square). Cut 6 inch squares of parchment paper and wrap each caramel, twisting the ends of the paper to close.

4 medium sweet potatoes

2 medium apples

4 Tbsp. butter or non-dairy substitute

1/3 cup Baba Yaga’s Apple Cider Syrup

1/2 tsp. salt

Place sheet of aluminum foil on bottom oven rack. Position second oven rack in middle of oven. Preheat oven to 375 degrees F.

Wash sweet potatoes and make a small slit on one side of each potato. Place potatoes directly on middle oven rack, slit side up. Bake 45-60 minutes or until soft. Remove from oven and let cool slightly. Decrease oven temperature to 350 degrees F.

While potatoes are baking, core, peel and slice apples 1/4 inch thick. Saute apple slices in 2 Tbsp. butter or substitute until tender. Set aside.

Peel cooked sweet potatoes and place in bowl. Mash together with remaining 2 Tbsp. butter or substitute, apple cider syrup, and salt. Stir in cooked apples.

Place sweet potato-apple mixture in ovenproof baking dish and cover with lid or foil. Bake 25-30 minutes.

8 cups of plain popped corn, unsalted

1 cup white sugar

1/3 cup Baba Yaga’s Apple Cider Syrup

2 tsp. vegetable oil

1/4 tsp. salt

Prepare a large, rimmed baking sheet by lightly oiling or lining with parchment paper. Set aside.

Place popped corn in large glass or ceramic bowl (not plastic). Bowl should be large enough so popcorn can be stirred easily without spilling over. Set aside.

Combine sugar, cider syrup, oil, and salt in small saucepan. Mix well.

Cook over medium-high heat, stirring often, until a candy thermometer registers 290 degrees F, about 6-8 minutes.

Remove from heat and pour over the popcorn. Quickly stir popcorn with spatula to coat evenly.

Transfer to the prepared baking sheet and spread coated popcorn to cool.

When cold, break into small pieces and store in airtight container.

1/3 cup olive oil

1 tsp. minced shallot

1/4 cup Baba Yaga’s Apple Cider Syrup

2 Tbsp. finely chopped peeled apple

1/4 tsp. salt

1/4 tsp. ground pepper

Combine all ingredients in a food processor or blender. Blend until smooth.

Serve over salad greens with sliced red onion and thin wedges of apples, or your favorite salad.

Forget about molasses — apple cider syrup adds outstanding flavor to our favorite picnic food. This recipe will make about 6-8 servings as a side dish.

1 lb. dried beans (California pea, Navy, Great Northern)

1/4 teaspoon baking soda

1/2 cup Baba Yaga’s Apple Cider Syrup

4 Tablespoons sugar

1 teaspoon dry mustard

1/2 teaspoon ground ginger

2 teaspoons salt

1/4 teaspoon black pepper

1 medium onion, cut in half from top to bottom

1 large, firm apple, peeled, cored, and diced into small pieces

Soak the beans overnight in enough water to cover them by 2 inches. The next day, drain them and place in a pot with the baking soda plus enough water to cover by 1 inch. Bring to a boil, then reduce the heat and simmer, uncovered, for 20 minutes, skimming any foam off as needed. Remove 1 cup of cooking water and set aside. Drain and rinse the beans, then place in a bean pot or slow cooker with onion halves.

Combine the syrup, sugar, mustard, ginger, salt and pepper. Gradually stir in the reserved cooking water. Pour over the beans and onions. Bake, covered, at 300 degrees in the bean pot, for 6-7 hours, or until done, stirring occasionally. A slow cooker will take about 6 hours, still covered and stirring occasionally. Add the diced apple during the last hour of cooking. If saucier beans are desired, add small amounts of water as needed.

*This apple beer, or graf, recipe is a work in progress from beermaking novices! Feel free to experiment and make it your own! This recipe will make about 2.5 gallons of apple beer. You will need jars or other containers to bottle your beer. We use about 10 quart jars.

5.5 g Nottingham yeast

0.25 lbs Crystal 60L

1/2 oz. torrified wheat

2.5 gal water (ended up being more like 2.75 gal because I didn’t take into account q.s.–ing the water and cider syrup)

1 lb extra light DME (I prefer amber ales and think this would make a nice one, but have to consider any caramelized flavor/color the cider syrup will add)

0.25 oz. pelleted Saaz hops

24 oz. apple cider syrup

Steep the 60L and torrified wheat in 1/2 gallon water at 155 degrees for 30 minutes.

Sparge with 1 quart water at 170 degrees.

Add DME and bring to a boil. Add hops and boil 30 minutes.

In a separate pot, add 24 oz. cider syrup to 2 gallons water and bring to a boil (just for sanitation; warm water is sufficient to blend the syrup with water).

Cool down wort to 70 degrees. Cool down syrup-water to 70 degrees.

Add both liquids to 3 gallon carboy and pitch yeast. Affix airlock with overflow tube and let sit in 64-68 degree conditions.

About two weeks later, it’s time to bottle (check specific gravity for precise timing):

Remove a cup of beer from carboy and boil briefly with 3/8 cup corn sugar. Pour into a vessel large enough to hold 2.5 gallons of beer, then siphon your beer into vessel. Siphon your beer into the sanitized bottles, jars, etc., leaving about an inch and a half of air space. Set the bottles in a warm place for a few days, then transfer to a cool, dark place for long-term storage. After a few weeks in bottles, start sampling and drink up!

Our orchard is located at 1259 Joyce Acres Road in Westfield, NC 27053. We are currently open by appointment, for special on-farm events, and off-site festivals.

You can find many of our orchard products, including apple cider syrup, in our online Etsy store. To visit, please click here or search for the shop name KordickFamilyFarm at http://www.etsy.com.

Directions from Pilot Mountain:

Traveling on US-52 North, take the exit 134 for Pilot Mountain, NC-268. Enter roundabout and exit to the first right onto S. Key St./NC-268. Take a left at the CVS stoplight to continue on NC-268. Turn right on Old Westfield Road. After about 6.5 miles Old Westfield Road dead-ends into NC-89. Take a right onto NC-89 at the stoplight. Go 3 miles, then take a left onto Frans Road. After a mile, take a left at the stop sign to continue on Frans Road. Take the first right onto Christian Road. Take the first right onto Joyce Acres Road and travel 1 mile to reach 1259.

Directions from Francisco:

Traveling west on NC-89, take a right onto Asbury Road. At the stop sign, take a left to continue on Asbury Road. After about a half a mile, take a left onto Joyce Acres Road, and travel about a half a mile to reach 1259.